KOSH: The Knowledge Graphs That Power Enterpret

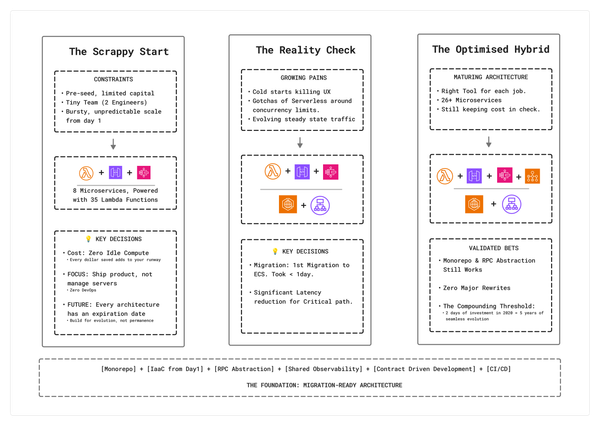

Introduction: Why Enterprises Need a Knowledge Graph

When we started Enterpret, the problem we set out to solve was clear and well‑scoped: make sense of customer feedback at scale. Feedback was everywhere — support tickets, surveys, reviews, calls — and teams were drowning in raw text with very little signal. Our early systems focused on ingestion, normalization, and analysis of feedback itself.

As we began working closely with deeply customer‑obsessed teams — product leaders, CX owners, and operators who actually drove decisions based on customer feedback — a pattern emerged quickly: feedback, by itself, is incomplete context.

At first, the solution seemed straightforward. We augmented feedback with user data and account data. Knowing who said something, which account they belonged to, and how valuable that account was immediately improved prioritization. A complaint from a high‑revenue customer carried a different weight than one from a long‑tail user.

But even that wasn’t enough.

Consider a simple but revealing example: customers at Walmart repeatedly complain about bathrooms being dirty. This isn’t a product bug. It isn’t a support workflow failure. It’s an operational problem, tied to specific stores, locations, shifts, and processes. Without store‑level or location‑level context, this feedback is almost impossible to route, prioritize, or solve meaningfully.

This was the realization that fundamentally changed how we thought about Enterpret.

The problem becomes even more interesting when you zoom out one level further. Dirty bathrooms don’t just generate complaints — they change customer behavior. Customers spend less time in the store. Shorter visits translate to fewer items discovered, lower basket sizes, and ultimately, lost revenue.

Suddenly, what looks like an operational hygiene issue is directly tied to business outcomes. But that connection is invisible if feedback lives in one system, operational data in another, and revenue metrics somewhere else entirely. Without a way to model and traverse these relationships, enterprises are left reacting to symptoms instead of understanding impact.

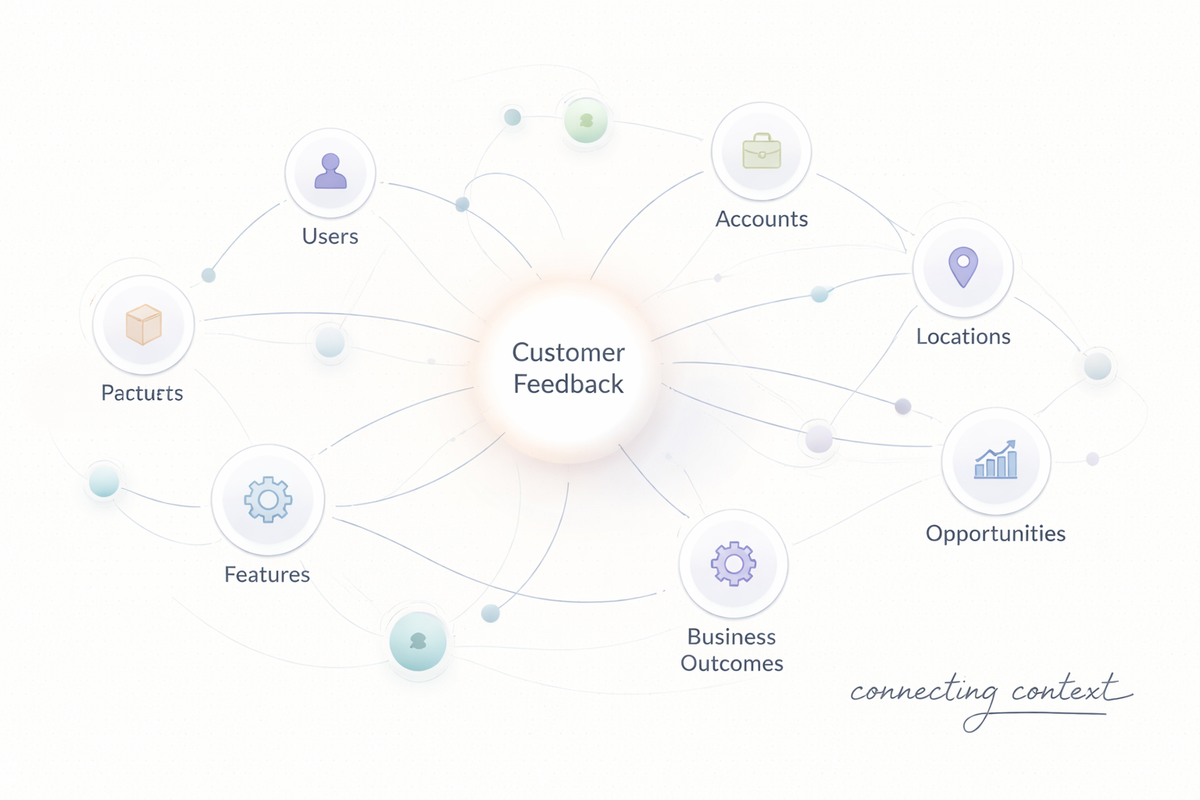

Customer feedback doesn’t exist in isolation. It lives inside a much larger web of business context — users, accounts, products, features, locations, org structures, operational entities, and outcomes. To act on the voice of the customer, enterprises need a system that can capture not just feedback and insights, but the entire domain‑specific context that surrounds them.

That system, for us, became KOSH.

The name KOSH comes from the Sanskrit word kośa, which means a repository or treasury. The idea resonated early on — the system was never meant to store just feedback, but to serve as a repository of facts, concepts, relationships, and knowledge that together represent how an enterprise actually operates.

KOSH is Enterpret’s internal knowledge graph. It represents the voice of the customer, grounded in business reality — a structured, evolving model of entities and relationships that allows teams to explore feedback in context, reason over connections, and drive real decisions.

This post dives into how KOSH is built, why we chose a graph‑first model, and the primitives that power Enterpret at scale.

From Feedback Analysis to Enterprise Intelligence

Enterpret began as a feedback analysis system. But as our customers' usage matured, the questions they wanted answered matured too — from investigative ("Why are enterprise admins complaining about SSO this week?"), to quantification ("How big is this issue across accounts, and what's the revenue exposure?"), to monitoring ("Alert me when high-value accounts mention churn-risk language").

A surprising thing happens when you build for all three: the core challenge stops being "how do we analyze feedback?" and becomes "how do we represent the enterprise domain so the system can answer arbitrary questions about it?"

That's where a knowledge graph becomes foundational.

Knowledge Graph as a Modeling Paradigm (Not a Database Choice)

When we say “knowledge graph” at Enterpret, we’re not talking about a graph database.

A knowledge graph is our data modeling and architecture paradigm — a way to represent domain context and business context so Enterpret can interpret, connect, and answer customer questions.

The database is an implementation detail.

This distinction matters because enterprises don’t have one access pattern.

- Investigative exploration often wants relationship traversal, neighborhood expansion, and contextual retrieval.

- Large-scale quantification wants fast scans, aggregations, and slicing over many dimensions.

- Search and discovery wants indexing — lexical, semantic, or hybrid.

No single storage engine wins across all of those.

So one of our guiding principles in building KOSH was:

Don’t couple the knowledge graph to a single access pattern.

KOSH is the source-of-truth model. Different projections of KOSH can be served from different systems depending on the workload:

- For heavy quantification (custom formulas, lots of slicing): a columnar/analytical store is often the best fit.

- For relationship-heavy exploration and certain retrieval flows: a graph store can be useful.

- For search (keyword + semantics): a vector or hybrid index is typically the right abstraction.

You can go far without a graph database. You can go far without a vector database. The point isn’t the vendor or the engine.

The point is that KOSH stays stable as a model, while the serving layer can evolve with product needs.

Why a Graph, Not Just Better Tables

If feedback lacks context, the instinctive response is to add more columns: account_id, user_id, plan, region, feature, taxonomy — with enough joins, any question should be answerable.

That approach works — until it doesn't. As enterprise data grows, three issues emerge:

- The domain is not fixed. New entities appear constantly — locations, opportunities, work items, experiments — often after the system is already in production.

- Relationships outnumber entities. Feedback doesn't just belong to an account; it references features, maps to themes, connects to opportunities, and evolves over time.

- Queries are not known upfront. The most valuable questions are exploratory. They emerge only after data exists.

Relational models optimize for predefined questions. Knowledge graphs optimize for unknown ones.

Core Primitives of KOSH

KOSH is built on a small set of primitives. We kept them deliberately minimal because KOSH needs to model wildly different enterprise domains without forcing every customer into the same rigid schema.

1) Objects

Objects are the fundamental units of the graph — you can think of them as node types. An object has an ID, a name, and a schema.

The schema has two parts:

- a static subset (fields we know we'll always need)

- a dynamic subset (fields that evolve as we see more customer-specific attributes)

In practice, an object definition looks like this:

Object: Account

├── Static Schema

│ ├── origin_record_id: STRING

│ └── name: STRING

└── Dynamic Schema (expanded at runtime)

├── metadata.salesforce.industry: STRING

├── metadata.salesforce.annual_revenue: FLOAT

├── metadata.salesforce.number_of_employees: INT

└── ... (80+ more fields from CRM integrations)

This "partially static, partially dynamic" approach avoids the two common failure modes: overly rigid schemas that don't match reality, and completely schemaless blobs that become impossible to reason about.

2) Records

Records are specific instances of an object — the concrete entities that actually exist.

If "Account" is an object, then "Walmart" is a record. If "Location" is an object, then "Store #1847 in San Jose" is a record.

Records carry field values for both static and dynamic schema components. They also carry version metadata, timestamps, and merge history (since records can be deduplicated over time).

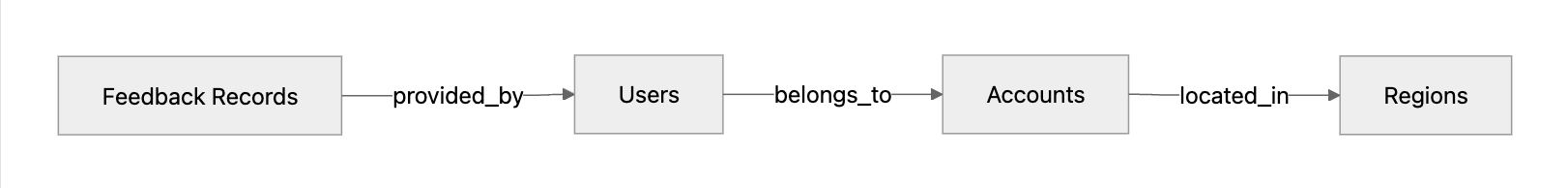

3) Relationships

Relationships connect records together. In the core graph, relationships are first-class edges — not foreign keys embedded inside records.

For example:

- a feedback record has an account,

- is provided by a user,

- refers to a product area,

- or connects to a downstream work item.

This separation is intentional. It allows relationships to be added or removed without rewriting records, to be derived from multiple sources, and to evolve as the understanding of the domain evolves.

How relationships are projected into analytics: The core graph treats relationships as edges. But our analytical store (ClickHouse) is a columnar database optimized for scans and aggregations — it has no native concept of edges.

So when projecting into the analytical layer, we materialize relationships as join tables with source_record_id, destination_record_id, and relation_type. This allows us to answer questions like "all feedback from enterprise accounts" using standard SQL JOINs, while the core graph retains edge semantics for traversal-heavy workloads.

Dynamic Schema Evolution

A core tension in modeling enterprise data is deciding what should be opinionated and what should remain flexible.

In KOSH, certain objects — like feedback records, accounts, users, and opportunities — behave as first-class primitives that power inference pipelines, analytics, and downstream workflows. For that to work, some attributes must always exist and must be strongly typed.

At the same time, enterprises are inherently heterogeneous. Feedback metadata looks different for every customer. Account properties vary wildly depending on CRM setup. New objects arrive with domain-specific attributes that Enterpret could not have predicted.

To reconcile this, every object schema in KOSH is split into static schema (opinionated, guaranteed to exist) and dynamic schema (evolves as new attributes appear).

Schema-on-Write, Not Schema-on-Read

Schema evolution in KOSH is schema-on-write. When new attributes are observed during ingestion, KOSH detects them at runtime, evolves the schema, and executes the required DDL so the data remains fully structured. We intentionally avoid storing arbitrary JSON blobs because read-time performance for analytics must remain predictable and fast.

How Type Inference Works

Every dynamic field is stored with its type encoded in the column name. For example:

location__s → STRING type

location__n → NUMERIC type

location__b → BOOLEAN type

If the same field appears with different types across records (e.g., a location field comes in as a string from one source and a number from another), we don't coerce or reject — we create both columns. During ingestion, we cast to the expected type where possible, but we never mutate existing column types.

This means a single logical field can have multiple typed representations:

Account Dynamic Schema:

├── metadata.customer_id__s: STRING (from CSV import)

├── metadata.customer_id__n: INT (from API sync)

└── metadata.region__s: STRING

The type is always trailing in the field name, making the schema self-documenting and allowing downstream systems to handle type variations explicitly.

Self-Healing Schema Sync

DDL events are partitioned by tenant and object so they execute in order. But more importantly, DDLs are self-healing: even if an event is missed, the next DDL event detects the delta between the primary store and the analytical projection, then executes DDL for everything in that delta.

This means schema drift between primary and secondary is eventually corrected without manual intervention.

What a Customer Knowledge Graph Looks Like

Before discussing how KOSH powers analytics and AI systems, it’s useful to ground the abstraction in something concrete.

Consider a simplified example of a large retail enterprise using Enterpret.

At ingestion time, feedback records enter the system as unstructured text. Over time, KOSH enriches and connects that feedback to surrounding business context.

A single feedback record may end up connected to:

- a User who submitted it,

- an Account the user belongs to,

- a specific Location or store,

- one or more Product Areas or features,

- an active Experiment or rollout,

- and downstream Insights or operational work items.

Conceptually, that graph might look like:

Feedback #81273

├── provided_by → User: U123

├── belongs_to → Account: Walmart

├── occurred_at → Location: Store #1847 (San Jose)

├── mentions → Feature: Checkout

├── part_of → Experiment: Self‑checkout v2

└── contributes_to → Insight: Long wait times

Each of these entities carries both static attributes and dynamic, customer‑specific metadata.

For example:

Account

- id

- name

- plan

- region

- metadata.* // dynamic

Location

- location_id

- country

- store_type

- attributes.* // dynamic

As more data is ingested — CRM updates, experiments, enrichment pipelines — new attributes and relationships are added without restructuring existing data.

Over time, the result is not a single table or dashboard, but a dense, evolving representation of the customer’s business domain.

This is the substrate on top of which Enterpret builds analytics, inference, search, and automation.

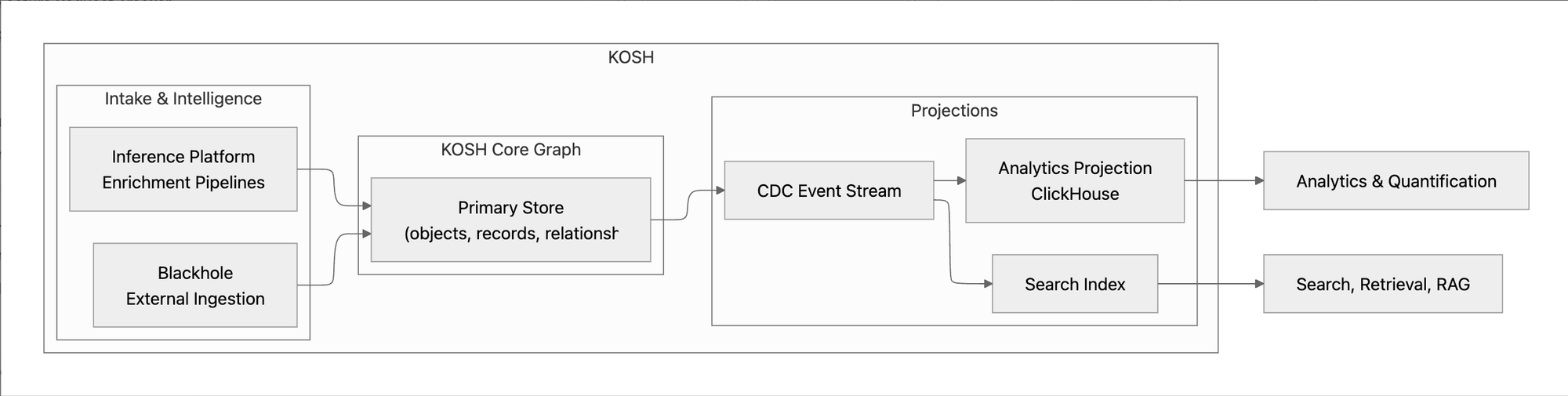

Building KOSH: Architecture and Design Choices

At its core, KOSH is a data-modeling system. It defines how enterprise context is represented, connected, and queried — but it does not generate data on its own. All data originates elsewhere.

Three Layers of Intelligence

Layer 1: The Core Graph exposes APIs to define objects and schemas, create and update records, and add or remove relationships. It is responsible for correctness, consistency, and modeling guarantees. This layer has no intelligence — it simply stores the current state.

Layer 2: System Intelligence consists of internal systems that populate and enrich the graph:

- External Ingestion (internally called Blackhole) synchronizes data from feedback platforms, CRMs, data warehouses, and support tools. It normalizes third-party data and maps it to KOSH objects.

- Internal Enrichment (the Inference Platform) runs near real-time pipelines that read from the graph, perform classification or extraction, and write enriched records and relationships back.

Layer 3: User Intelligence allows customers to extend the graph through taxonomy management, enrichment configuration, and user-defined transformation functions.

The Data Lifecycle

Across all layers, the lifecycle is consistent:

- Data enters via external ingestion or internal generation

- Base objects and records are created

- Enrichment systems attach additional context

- Change events (CDC) propagate updates to downstream projections

- Workloads consume optimized views, while KOSH remains the canonical source of truth

End-to-End Data Flow

Data flows through KOSH in five steps:

1. External Ingestion: Data enters from feedback platforms, CRMs, and support tools via Blackhole, which normalizes and maps it to KOSH objects.

2. Core Graph Writes: Data is written using core primitives — objects, records, and relationships. KOSH stores only the latest state.

3. Enrichment: The Inference Platform runs near real-time pipelines that classify feedback, extract signals, link entities, and generate derived insights — all written back as new records and relationships.

4. CDC Propagation: Every mutation emits a change event describing the previous and new state. These events keep all downstream systems synchronized.

5. Projection into Read Models: CDC events are consumed by projection pipelines, each optimized for a specific workload:

- Analytics (ClickHouse): Every object becomes a table, every record becomes a row, dynamic attributes expand into columns via runtime DDL, and relationships materialize as join tables. We intentionally maintain a ~15-minute freshness window to optimize for batch writes over extremely wide tables.

- Search & Retrieval: Parallel projections feed keyword lookup, semantic search, and RAG-style context expansion.

The critical idea: no projection owns the truth. KOSH remains the single source of truth for schema, entities, relationships, and meaning. By separating modeling from serving, we can evolve how data is consumed without rewriting how it is understood.

How KOSH Powers Enterpret

To understand why this architecture matters, it helps to see how it behaves when real users ask real questions.

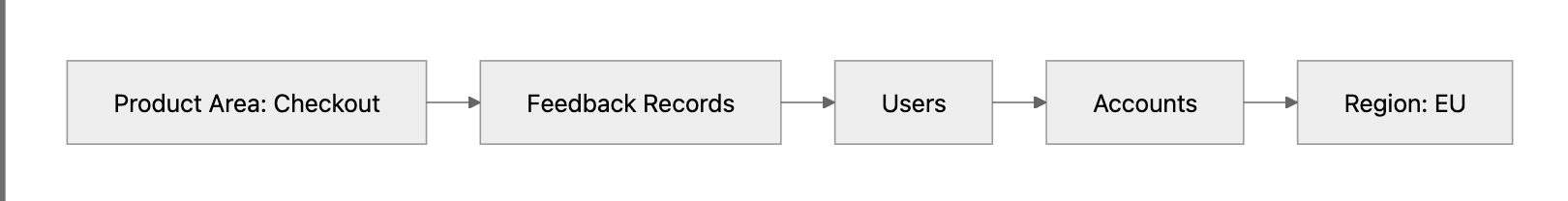

Journey: Why Did Checkout Complaints Increase Last Week?

A product manager logs into Enterpret with a simple question:

Why did checkout complaints spike last week?

This question doesn't begin with a dashboard or predefined metric. It begins with context.

Step 1: Feedback enters the graph as unstructured text with basic metadata (source, timestamp, user_id, account_id).

Step 2: Enrichment pipelines classify the feedback — inferring it relates to "checkout" — and add a relationship to the Checkout taxonomy node. The checkout node isn't a label; it's a first-class object with identity, hierarchy, and its own relationships.

Step 3: Navigation begins from taxonomy. Because taxonomy exists inside the graph, the PM starts from the Checkout node and traverses to all related feedback. Applying a time filter reveals the spike. Now they know what changed.

Step 4: Slicing happens through existing relationships. Each feedback record is already connected to users and accounts. The PM can ask: Is the spike isolated to a geography? Concentrated in enterprise accounts? Correlated with a rollout?

Checkout

→ Feedback Records (filtered: last week)

→ Users

→ Accounts

→ Regions (EU)

Step 5: From anomaly to explanation. The spike originates primarily from European accounts — tied to a regional rollout. What began as a volume anomaly becomes a contextual explanation.

No new pipelines were written. No new schema was introduced. The answer emerged from navigating relationships that already existed in KOSH.

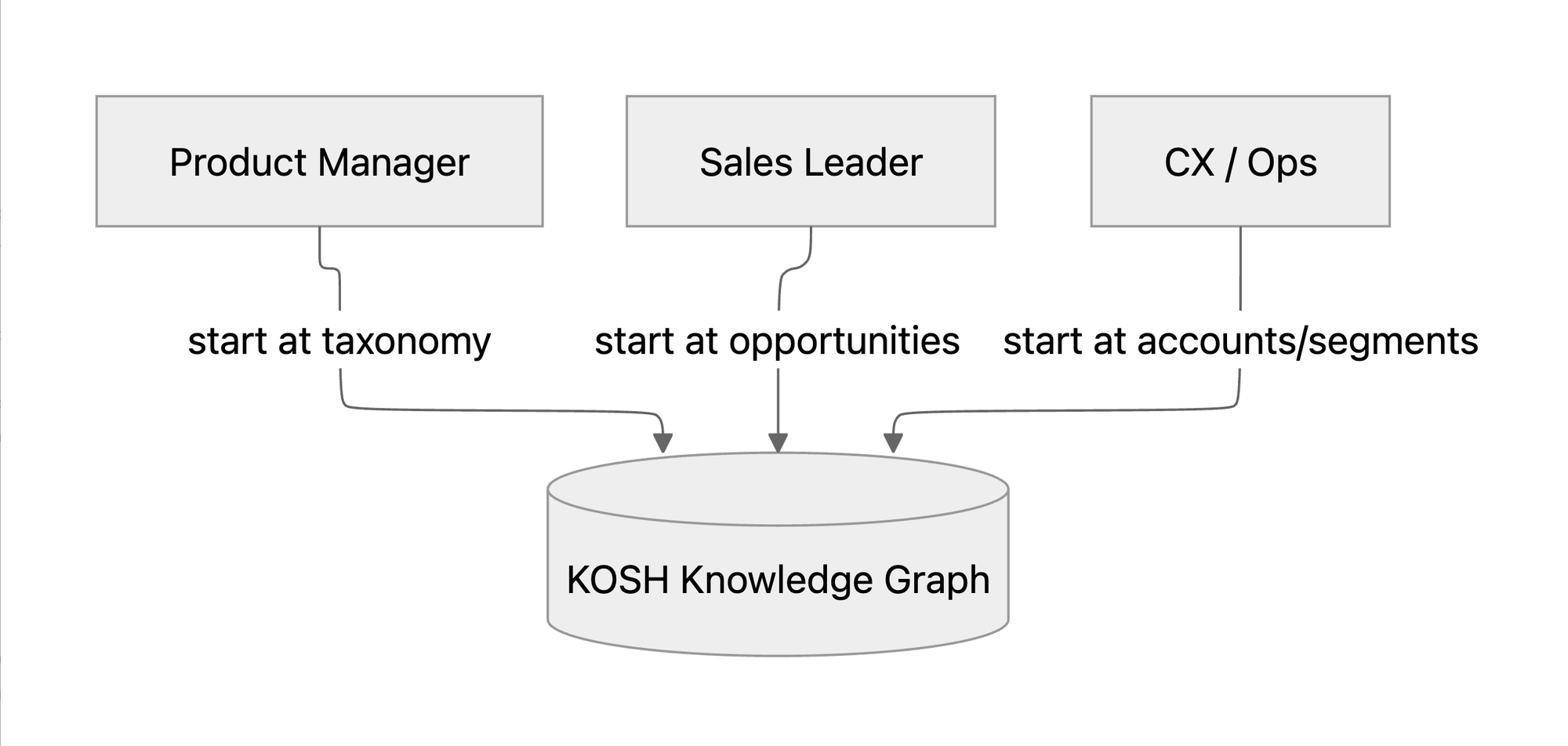

Different Entry Points, Same Graph

The same pattern works for other roles:

- Sales leaders start from Opportunities, traverse to feedback, and surface feature gaps or competitive signals from lost deals.

- CX teams start from Accounts or segments and identify patterns in support interactions.

The graph remains constant. Only the entry point changes. KOSH provides the shared language that allows Enterpret to support investigative analysis, large-scale quantification, monitoring, and AI-powered workflows — all without duplicating data models.

Lessons Learned

Building KOSH forced us to confront problems that don't usually appear when designing traditional data platforms. Many of the most important lessons only emerged once the system was operating at real enterprise scale.

1. Consistency Is Engineered, Not Given

Designing objects, schemas, and relationships is comparatively straightforward. The hard part is keeping multiple representations of that model consistent.

KOSH projects the same knowledge graph into multiple downstream systems, each optimized for a different access pattern. This means the system cannot be fully synchronous — the graph is eventually consistent by design.

Once we accepted that constraint, a large class of problems followed naturally:

- Projections cannot assume strict ordering of events

- Schema updates may arrive before the records that depend on them

- Links may be generated before both sides of the relationship exist in every downstream projection

We address this through version-based conflict resolution — if a stale update arrives, it's rejected based on version number. The same applies when syncing to the analytical store: we always retain the latest version and discard out-of-order updates.

DDL operations are self-healing: even if a schema update event is missed, the next DDL event detects the delta between primary and secondary stores and executes DDL for everything in that gap. This means temporary inconsistencies correct themselves without manual intervention.

2. Analytics Dominated the Engineering Surface Area

The majority of our engineering investment went into analytical projections. Tenants routinely execute queries that:

- scan tens or hundreds of millions of rows,

- slice across dozens of dimensions,

- and operate over schemas with hundreds of attributes.

We were surprised by how wide objects became in practice — some accumulating 500–700 distinct attributes over time. This isn't hypothetical: our Account object for one customer expanded to 800+ dynamically inferred fields from their Salesforce integration alone.

Supporting this required significant innovation:

- Dynamic DDL execution without downtime

- Time-based partitioning over extremely wide tables

- Intentional freshness windows (~15 minutes) to batch writes efficiently

- Query planning over schemas where the shape isn't known until runtime

Because analytics is our core workload, we operate our own ClickHouse cluster rather than relying on a managed offering. This introduced operational overhead but gave us control over data layout, partitioning strategy, and query behavior at high volumes.

3. The Incidents That Taught Us the Most

The most painful lessons came from real incidents:

Data sync failures: The most common class of issues involved data getting out of sync between primary and secondary stores. A DDL event would fail silently, and the analytical projection would drift from the source of truth. Self-healing DDLs were our response — the system now auto-corrects on the next successful event.

Queue clogging: A single malformed DDL event or an unexpectedly large batch could clog the event queue, creating cascading delays across all tenants. We now partition events by tenant and object, ensuring one customer's schema explosion doesn't block another's writes.

Noisy neighbors: Because we run a shared ClickHouse cluster, one tenant's expensive query could impact others. We've invested heavily in data paritioning, query optimisation, intelligent materialisation — but this remains an area of active work.

4. Operating at Scale Changes Every Assumption

At steady state, KOSH processes hundreds of millions of records and updates per day.

At that volume:

- Schema growth is unbounded

- Query shapes become unpredictable

- Small inefficiencies compound rapidly

Design decisions that look minor early on — how schemas evolve, how partitions are chosen, how updates are applied — become existential at scale. KOSH forced us to think less like application engineers and more like platform engineers.

Closing Thoughts

KOSH was not built to be a database, an analytics engine, or an AI system.

It was built to be a living representation of enterprise context — one that evolves alongside the business it models.

Customer feedback is powerful only when understood in the world it exists in: the users who provide it, the accounts that generate it, the products it refers to, and the operational reality that shapes outcomes.

By separating modeling from storage, and meaning from access patterns, KOSH allows Enterpret to support a wide range of workflows — from investigation and quantification to monitoring and AI-powered reasoning — without fragmenting the underlying truth.

As enterprises continue to generate more signals, more metadata, and more context, systems built around static schemas and predefined queries will increasingly fall behind.

Knowledge graphs are not a silver bullet — but for domains defined by evolving relationships and unknown questions, they provide a powerful foundation.

KOSH is our attempt to build that foundation.

In future posts, we’ll dive deeper into the systems that sit around KOSH — including Blackhole, our external ingestion engine, and our Inference Platform, which powers large-scale near real-time enrichment on top of the knowledge graph — along with the trade-offs involved in scaling each.