The Unorthodox Path: How We Built Enterpret

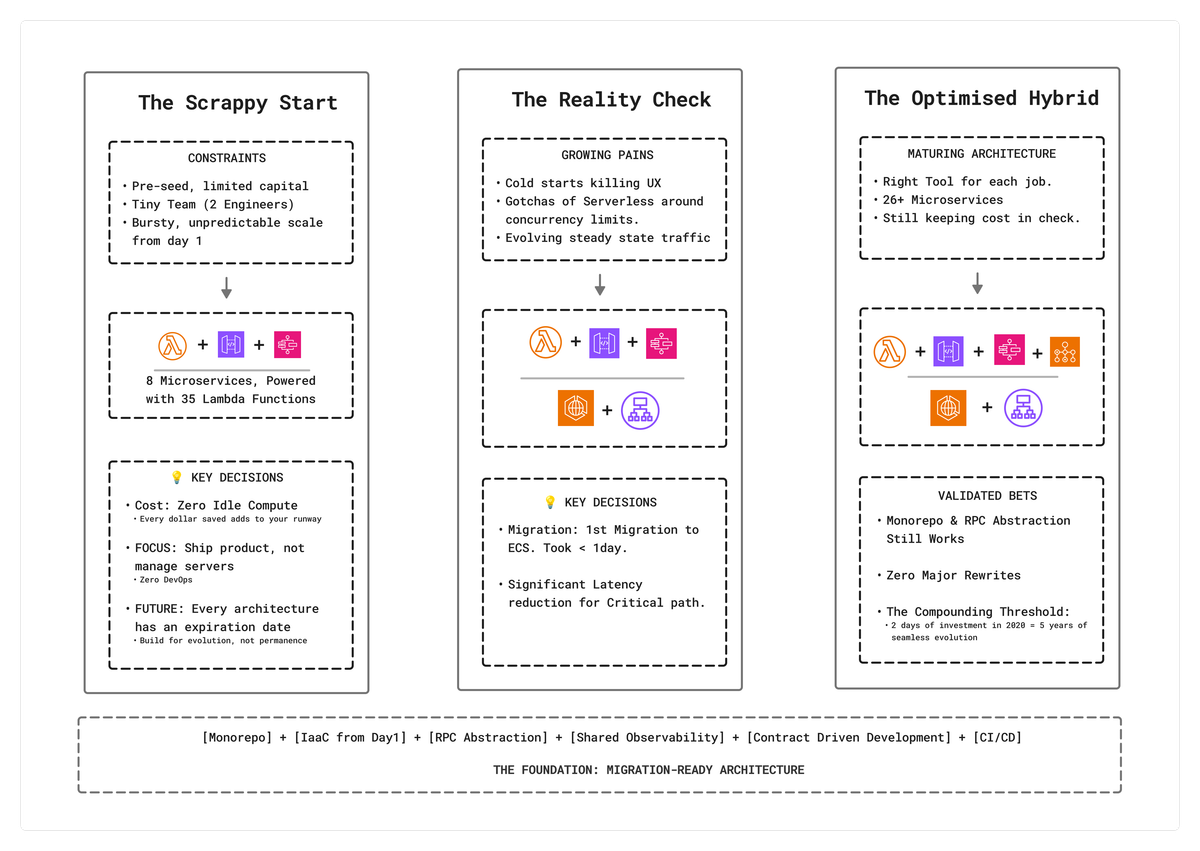

Discovery: The Moment We Chose Serverless

Every startup has that moment of reckoning when technology meets necessity. For us, it wasn't a clean spreadsheet decision. It was a story of discovery.

We were pre-seed, short on capital and long on ambition. Our constraints were clear: cost, team size, and scalability. We had a super tiny engineering team (just two engineers and an intern) and we wanted to focus every ounce of our energy on product velocity, not infrastructure management. We didn't have the luxury of always-on compute, and engineering bandwidth was limited enough that maintaining clusters or nodes was out of the question.

We sat together, whiteboarding our first architecture, and realized our compute pattern looked nothing like a typical SaaS app. Enterpret ingests massive volumes of customer feedback data, and most of our compute happens asynchronously; processing, enriching, and indexing that feedback for downstream insight generation. The synchronous, user-facing path was relatively light, but ingestion could be extremely bursty. When a customer triggered a large sync or a public event drove a spike in feedback, workloads would surge and disappear just as quickly.

That spikiness meant we needed real-time horizontal scalability, not just auto-scaling "eventually." The more we debated ECS, EC2, or even a single monolith, the clearer it became: managing servers would slow us down before we even started. ECS could scale, but not instantly. We didn't want to pay for idle compute, nor did we want to manage scaling manually.

Lambda felt like the scrappy, scalable ally a small team could trust: pay-per-execution, zero idle cost, and near-instant elasticity. That moment, when the lightbulb went off that serverless fit our use case perfectly, set the tone for how we would build Enterpret: make deliberate, data-driven bets, even if they seem unconventional.

We launched with around 8 microservices, comprising roughly 35 Lambda functions, built by 2 engineers and an intern. It was minimal, but fast, and it worked. The early decision to go all-in on serverless wasn't just pragmatic. It reflected our emerging philosophy as a team. We wanted to optimize for speed, simplicity, and cost-efficiency while retaining the flexibility to evolve.

And from the start, we designed with that flexibility in mind. We structured our microservices so that if a workload ever outgrew Lambda, migration to ECS would be effortless. That separation of application from deployment mechanism, keeping business logic decoupled from hosting, would prove crucial as we scaled. But we're getting ahead of ourselves. First, we needed to build the infrastructure that would let us scale development as easily as we scaled compute.

Architecture: Building for Evolution

Once we committed to serverless, we needed a way to keep order amid growing complexity. We needed a system that would let us scale development as easily as we scaled compute. What started as a few Lambdas quickly became an ecosystem, and we knew consistency and clarity had to become our north stars.

From the beginning, Enterpret’s engineering culture valued consistency, simplicity, and strong contracts over tooling fads. We built a Go monorepo: a single repository housing all backend microservices, shared libraries, and infrastructure code. Think of it as a well-organized city where every service has its neighborhood but shares the same utilities.

The Structure

backend-monorepo/

├── code/ # All microservices

│ ├── shared/ # Common code across services

│ │ ├── lib/ # Utility libraries

│ │ │ ├── errors/ # Standardized error handling

│ │ │ ├── rpc/ # Core RPC abstraction

│ │ │ └── [...] # Other shared libraries

│ │ │

│ │ ├── idl/ # Protocol buffer definitions

│ │ │ ├── customer-service/

│ │ │ │ ├── entities.proto # Domain models

│ │ │ │ ├── events.proto # Event contracts

│ │ │ │ └── rpc.proto # RPC definitions

│ │ │ └── [...] # Other service contracts

│ │ │

│ │ ├── gen/ # Generated protobuf code

│ │ │ ├── customer-service/

│ │ │ │ ├── entities.pb.go

│ │ │ │ ├── events.pb.go

│ │ │ │ ├── rpc.pb.go

│ │ │ │ └── rpc_iface.pb.go # Interface for server/client

│ │ │ └── [...]

│ │ │

│ │ └── gen-clients/ # Generated RPC clients

│ │ ├── customer-service/

│ │ │ └── client.go # Implements rpc_iface

│ │ └── [...]

│ │

│ ├── customer-service/ # Example microservice structure

│ │ ├── entrypoints/ # Deployment entry points

│ │ │ ├── lambdas/ # Lambda handlers

│ │ │ └── ecs/ # ECS containers

│ │ ├── src/ # Business logic

│ │ │ ├── config/ # Service configuration

│ │ │ ├── handlers/ # Request handlers

│ │ │ ├── services/ # Business logic layer

│ │ │ ├── repositories/ # Data access layer

│ │ │ ├── gateways/ # External service clients

│ │ │ └── rpc/ # Generated server (implements rpc_iface)

│ │ ├── staging.yaml # SAM template for staging

│ │ ├── production.yaml # SAM template for production

│ │ └── Makefile # Build and deploy commands

│ │

│ ├── edge-server/ # Frontend-facing API server

│ ├── kosh/ # Knowledge graph engine

│ └── [20+ other services...]

│

├── scripts/ # Build and deployment tools

└── .github/ # GitHub Actions CI/CD

This layout gave us atomic control over the entire backend ecosystem. One commit could update an API contract, regenerate clients, update services, and deploy, all in sync. It also ensured a shared language and tooling for every engineer, new or old.

Why Monorepo?

The monorepo allowed us to:

- Standardize services easily. Common abstractions for IDLs, RPCs, and shared libraries live in one place and evolve together. Standardized error codes and logging formats across all services made debugging distributed issues dramatically easier: one error format, one log structure, one way to trace requests across the entire system.

- Make cross-service changes in a single PR. Updating a data model used by multiple services happens in one commit, review, and deployment cycle.

- Refactor fearlessly across boundaries. IDE refactoring works across all services, catching breaking changes at compile time.

- Streamline deployments and CI/CD. One pipeline for all services, shared deployment patterns, and the ability to deploy related services together when breaking changes span multiple boundaries.

Today, our monorepo houses 26 microservices, grown from the original 8 as our team and product surface expanded. Each service remains independently deployable yet shares common infrastructure and patterns. We deploy multiple times a week, with necessary deployments happening at least twice weekly.

Tooling and Developer Experience

As our codebase expanded, the developer experience became both our shield and our accelerator. With a simple Makefile command, a developer could run, test, and deploy a service end-to-end. The tooling stayed out of the way, letting engineers focus on the problem at hand.

For infrastructure, we leaned on AWS SAM (syntactic sugar for serverless on CloudFormation) and CloudFormation as our IaC foundation, which made rollbacks and replication surprisingly painless. We stuck to simple Makefiles for builds and leveraged GitHub Actions for CI/CD. With Grafana and CloudWatch for monitoring, every commit had a predictable path from code to production. In practice, that meant developers could ship confidently multiple times a week, knowing the system would hold steady.

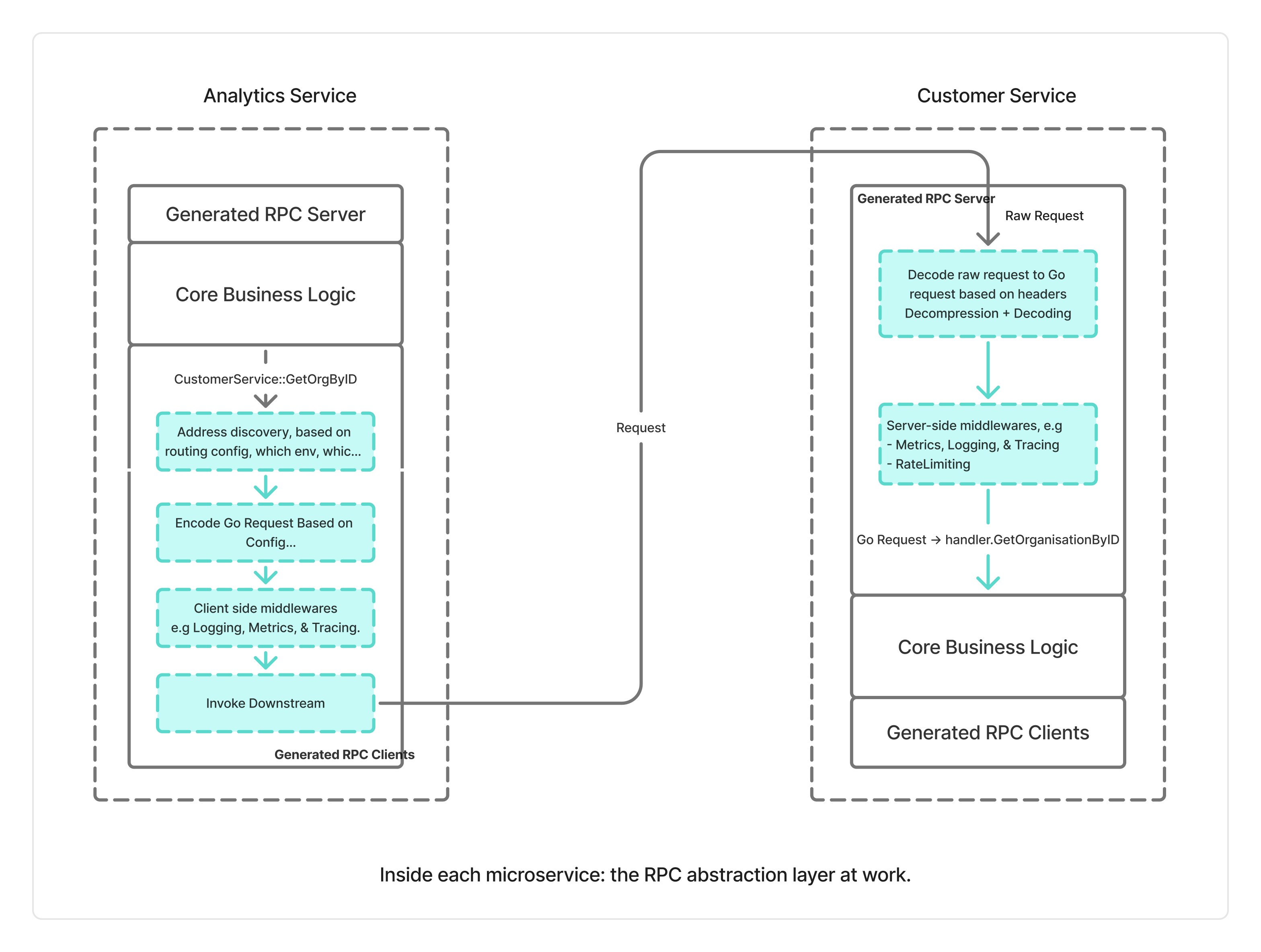

We followed contract-driven development with Protobufs and built our own RPC abstraction layer, a deliberate choice born out of early constraints. AWS API Gateway doesn't natively support gRPC, and we needed binary-over-HTTP support for efficient payload handling with Lambda. Rather than forcing gRPC through complex workarounds or locking ourselves into a single protocol, we built an abstraction that supports multiple encodings: protobuf binary over HTTP (base64-encoded), JSON for clients without protobuf support and ad-hoc experimentation, and gRPC compatibility for future migration paths.

This wasn't about reinventing the wheel. It was about operational simplicity and extensibility. The abstraction allowed us to leverage API Gateway's scalability with Lambda while keeping our options open. As a bonus, it enabled powerful extensions over time: payload compression using zlib, distributed tracing, metrics collection, and service discovery, all without requiring changes to individual services. Our RPC abstraction generated the entire server and client model code from Protobuf definitions, ensuring that service owners only needed to implement business logic. That abstraction, built in our first year, still powers our services today.

Of course, not everything was smooth sailing. Early on, we ran into a critical incident: uncontrolled Lambda concurrency consumed our entire account limit, starving critical services and causing outages. We learned the hard way that concurrency limits aren't optional. They're essential. From that moment forward, we enforced explicit concurrency controls in our Infrastructure-as-Code, preventing any single service from monopolizing compute resources. Debugging distributed systems through CloudWatch wasn't for the faint-hearted either, but even those frustrating experiences sharpened our discipline.

The result wasn't just automation; it was freedom to move without fear. Engineers could ship fast knowing the system would catch them. This was a rare luxury in the early days of a fast-growing startup.

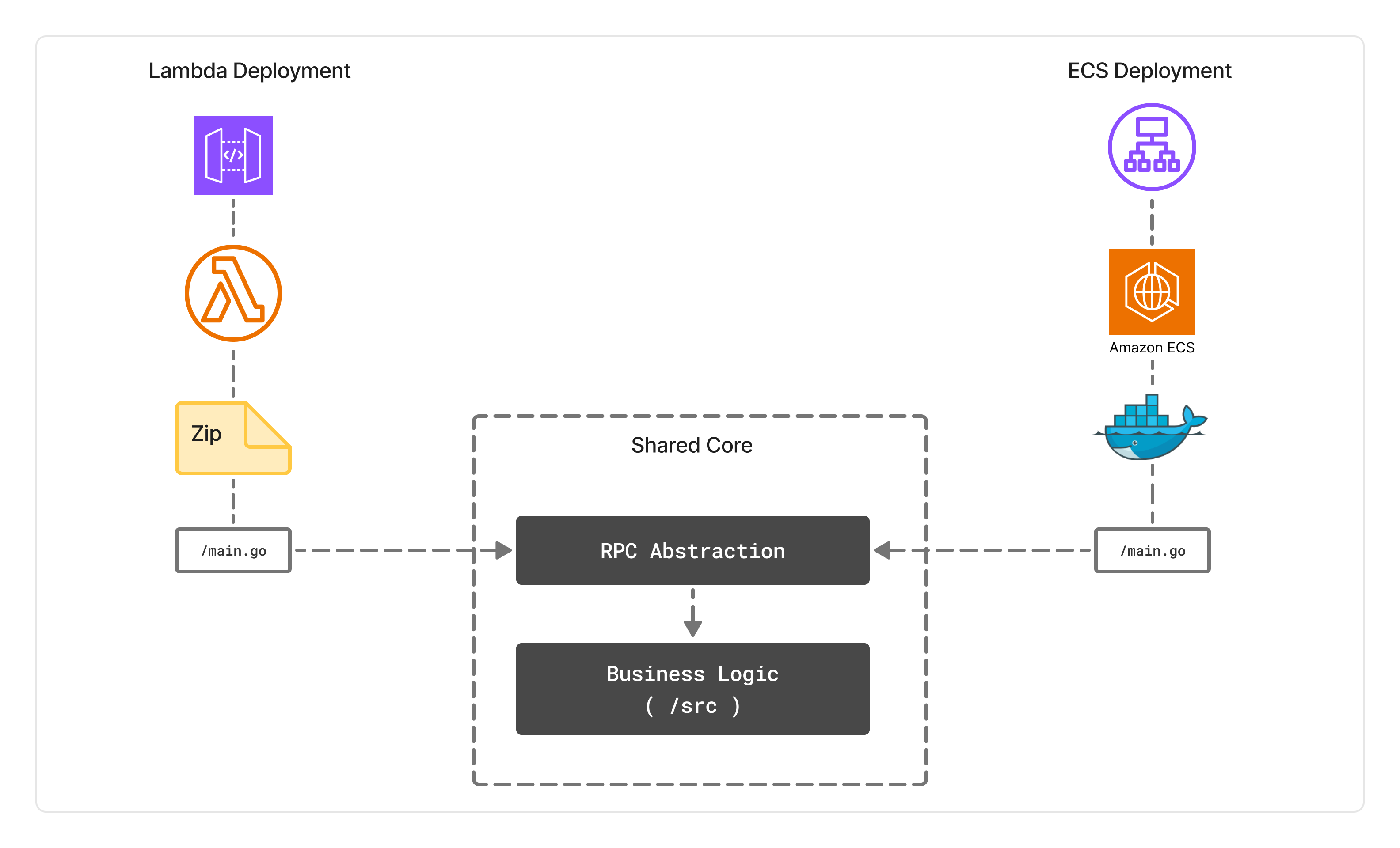

Migration by Design

A crucial benefit of this setup was decoupled deployment. Migrating a Lambda-based service to ECS required changing only the IaC template and switching from a Lambda handler to a Docker entrypoint. Often a one-hour change. That foresight of separating app logic from hosting allowed us to grow without rewriting.

Here's what that looked like in practice. Every service follows a consistent structure where business logic lives in src/, and deployment mechanisms live in entrypoints/:

kosh/

├── entrypoints/

│ ├── lambdas/rpc-server/main.go # Lambda entrypoint

│ └── ecs/rpc-server/main.go # ECS entrypoint

└── src/ # Business logic (unchanged)

├── services/

├── repositories/

└── handlers/

Both entrypoints share the same dependency injection and router setup. The only difference is how they're invoked:

// Lambda: entrypoints/lambdas/rpc-server/main.go

router := p.Router.Init(p.Config)

ginLambda := ginadapter.New(router) // Wrap for Lambda

lambda.Start(func(ctx, req) {

return ginLambda.ProxyWithContext(ctx, req)

})

// ECS: entrypoints/ecs/rpc-server/main.go

router := p.Router.Init(p.Config)

g := router.Init(cfg)

g.Run(":8080") // Just start HTTP server

Same business logic. Same dependency injection. Same router. The only difference is the three-line wrapper around it. That's what made migrations feel like reconfiguration, not rewrites. Sometimes small investments allow you to run fast for long term.

Resource Efficiency and Learnings

We were always hyperconscious about cost, especially in the early days. Memory allocation became one of our key optimization targets, as Lambda pricing scales with it. We learned early that most services didn't need much. Go's optimized binaries were a perfect fit. The language's efficiency meant we could run many services on minimal memory. A significant number of our Lambdas run on just 128MB of memory, keeping costs down without sacrificing performance.

Looking back, this phase taught us more than any technical manual could. Our RPC abstraction, migration-ready architecture, the monorepo structure, and yes, our obsession with cost: these weren't just technical choices. They became part of our engineering DNA. Each incident and constraint we faced made us sharper, reinforcing a culture of ownership and reflection. We learned that small, thoughtful investments in tooling and design compound over time. The systems we built could evolve without rewrites, migrate without drama, and scale without surprises. But scale has a way of revealing new edges.

Reality Check: When Serverless Stopped Being Enough

No technology decision lasts forever. As Enterpret grew, we began to see the edges of serverless, not as failures, but as signs that our architecture was maturing. The very elasticity that helped us move fast in year one began to show friction as workloads diversified and scale patterns evolved.

When We Hit the Limits

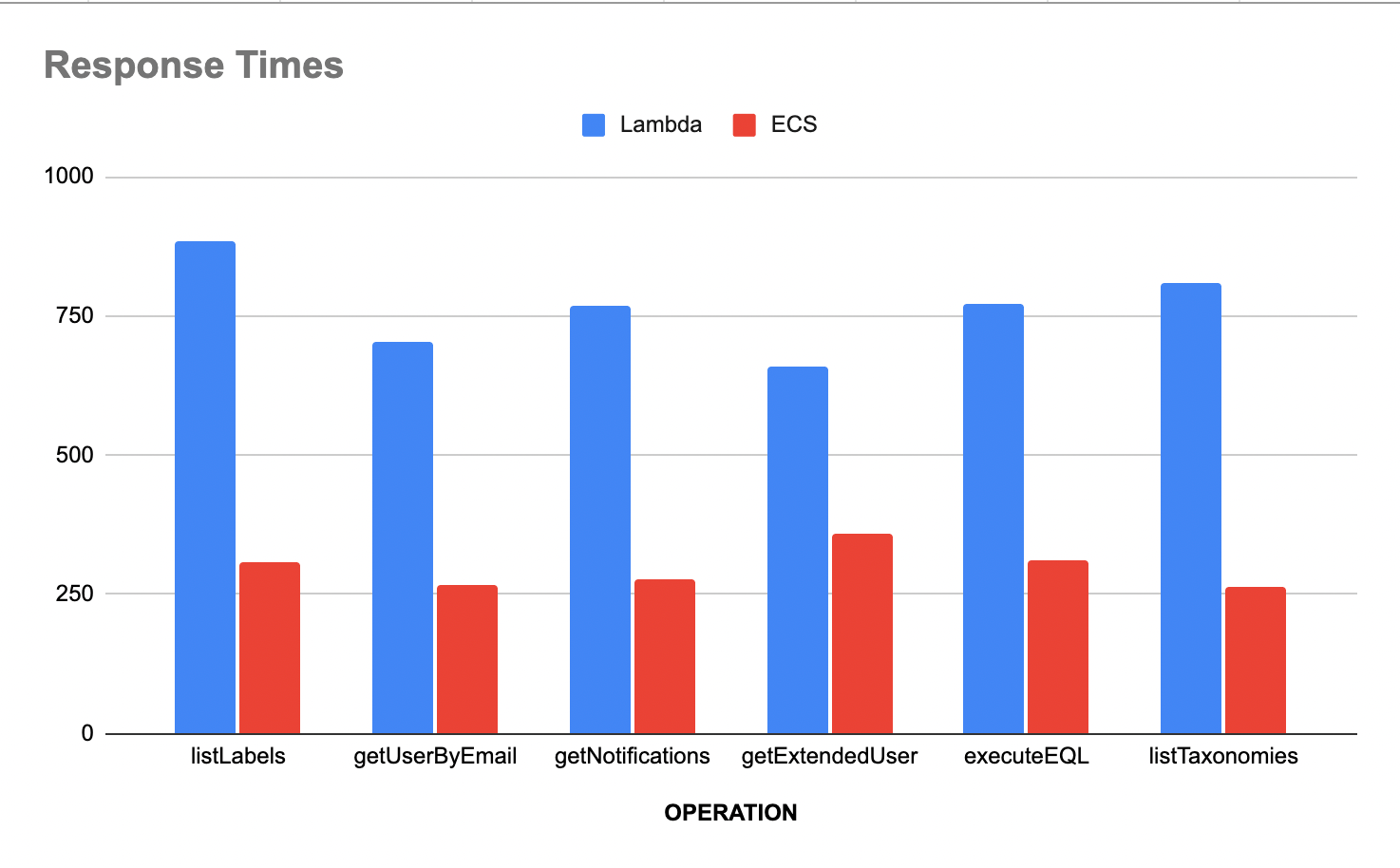

Our first real constraints emerged in high-concurrency, latency-sensitive workloads, particularly on our frontend analytics dashboards. These dashboards generated sudden surges of parallel queries that needed to return fast. Cold boot times on Lambda were adding significant latency to our critical path. Provisioned concurrency could have solved it, but our UI's access pattern required many concurrent parallel calls due to the analytics nature of the product, making always-warm Lambdas cost-prohibitive for predictable, consistent traffic.

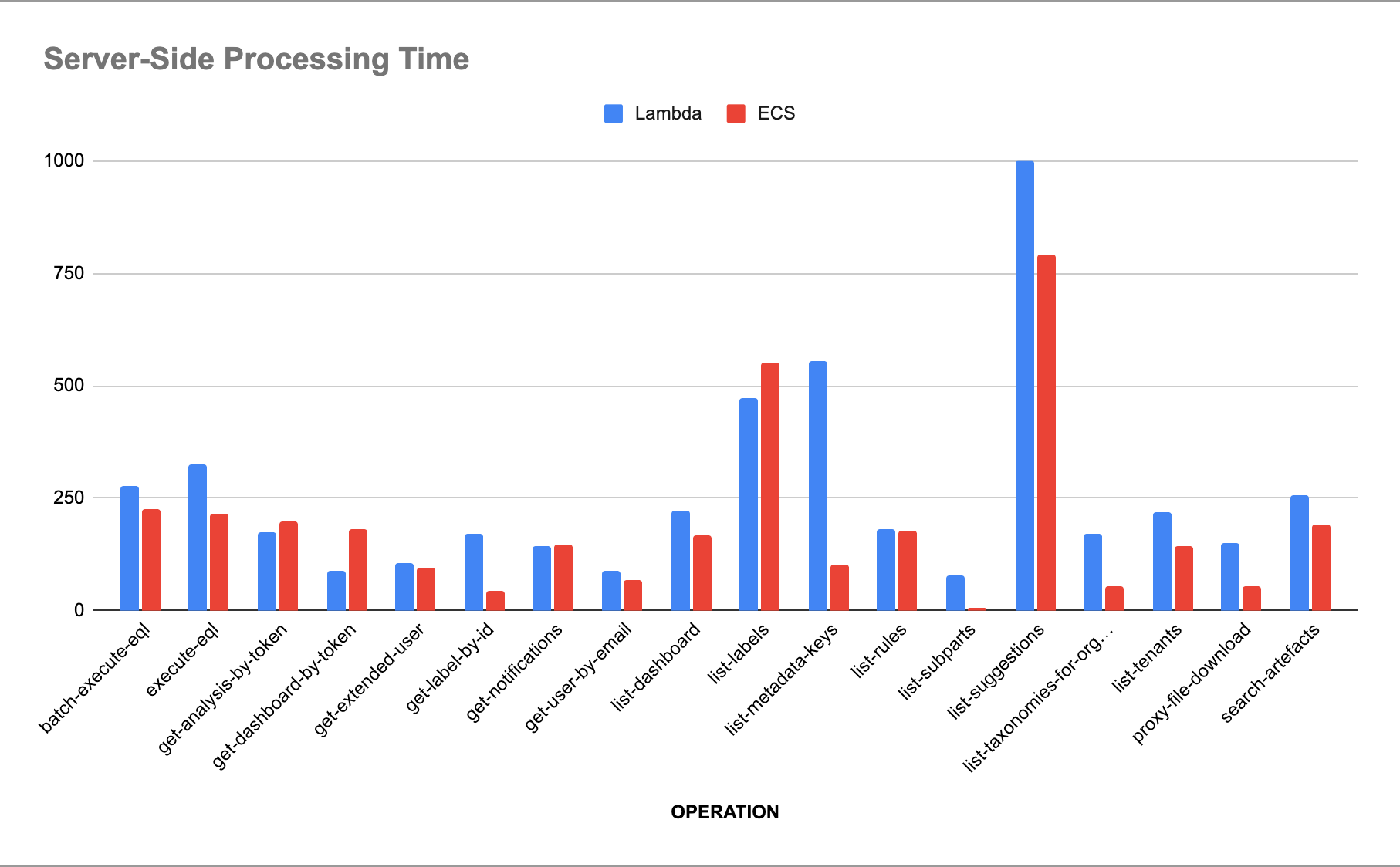

So we moved these components to ECS, where we could control scaling events more deliberately.

Next came the runtime limits. Lambda's 15-minute execution ceiling worked beautifully for most of our asynchronous workloads, but certain jobs like report generation and data exports needed more breathing room. These weren't critical paths, but they required reliable, long-running compute. Our solution wasn't to overprovision ECS; instead, we leveraged AWS Batch, backed heavily by spot instances, for extreme cost efficiency. For non-critical workloads, spot instances were a game-changer. We pushed costs down dramatically while maintaining reliability through AWS's automatic spot replacement. That one architectural choice slashed our compute costs for these workloads significantly.

Then there were payload constraints. Lambda enforces size limits on both input and output. In rare cases, responses exceeded the 6 MB threshold and failed silently, an insidious failure mode. We learned to offload these payloads to S3 and return signed links or multipart responses. It was an elegant workaround, but it underscored that Lambda isn’t ideal for data-heavy synchronous APIs.

And finally, API Gateway timeouts, capped at 29 seconds. This was a reasonable safeguard for 99.9% of our RPC calls, but a few long-running APIs struggled under it. Instead of switching to Application Load Balancer–based compute, we re-engineered request batching and optimized single RTT performance. It worked, but it reminded us that understanding your platform's constraints is as important as designing for its strengths.

The Migration Pattern

We designed for migration from day one. Not because Lambda would fail us, but because workloads evolve. The key was making migration a configuration change, not a rewrite. Over the years, we've learned to recognize the signals:

When cold boots hurt critical path latency and provisioned concurrency doesn't help. This happens when your access patterns require many concurrent requests (like analytics dashboards) where keeping everything warm becomes cost-prohibitive.

When traffic becomes steady enough that Lambda is no longer cost-efficient. The elasticity tax makes sense for bursty workloads, but once you hit consistent baseline traffic, ECS becomes cheaper. We watched this tipping point carefully.

When workloads need long-running execution. Lambda's 15-minute limit is reasonable, but report generation, data exports, or batch processing need more. AWS Batch on spot instances became our go-to for these non-critical, long-running jobs, dramatically cheaper than always-on compute.

When payload sizes or API timeouts become constraints. Lambda's 6MB input/output limits can fail silently. API Gateway's 29-second timeout is reasonable for most calls but limiting for complex operations. If you're constantly working around these limits, ECS with a load balancer gives you back control.

When you need stateful processing or persistent connections. Lambda's stateless nature and API Gateway's limitations make websockets and server-sent events challenging. Services requiring real-time connections or stateful stream processing naturally fit better on persistent compute.

Our edge-server ( which serves all our UI traffic ) migration exemplified this pattern. Within our second year, cold boot latency was killing our frontend experience. Our UI's analytics nature meant dozens of parallel queries per page load. Provisioned concurrency would've been prohibitively expensive. We migrated to ECS, and since our architecture already separated deployment from application logic, it took less than a day.

But we didn't just move compute. Our initial deployment was limited to US regions while our customers were worldwide. We added AWS redundant networking for efficient global routing. The impact was substantial: latency improved noticeably for our global user base, while compute costs on these now-steady workloads fell meaningfully.

We repeated this pattern as customer growth turned other bursty services into steady-state ones. The key was expecting these migrations years in advance, keeping infrastructure designed so migration wasn't a rock to move, but a smooth transition. It was never a rewrite, just a reconfiguration.

Cultural Takeaways

This phase taught us something far deeper than architectural nuance: small, thoughtful decisions compound.

We've learned to recognize the compounding threshold: the point where a modest upfront investment unlocks systems that evolve rather than break. One day gets you a hack. A hundred gets you perfection. Two days of thoughtful design? That's what compounds.

Take Blackhole, our data ingestion system. We could have hard-coded our first integrations in a day, or spent months building the "ultimate" framework. Instead, we took a few days to build abstractions that let each new source be a contained module without touching the core engine. Five years later, it's powering 50+ integrations (Slack, Zendesk, social media, surveys) without a single rewrite. That's the compounding threshold in action. But that's its own story.

This philosophy is why our migrations from Lambda to ECS felt effortless. We had invested just enough in decoupling deployment from application logic that changing compute was a configuration update, not an architectural overhaul. Below the threshold, we'd be rewriting services. Above it, we'd have wasted time on premature optimization. At the threshold, migration was just another Tuesday.

Many of the systems we wrote in Enterpret's first year are still running today. Not just running, but thriving. They've evolved, scaled, and adapted because we found that compounding threshold early and stuck to it.

Would We Do It Again?

Absolutely. Serverless gave us speed, cost control, and focus when we needed them most. The architecture choices we made (the monorepo, the RPC abstraction, the migration-ready design) would all stay the same.

But we'd also be more cautious about force-fitting workloads that don't belong on Lambda. Early on, one of our data collection services required long-running execution, so we stitched it together with AWS Step Functions and checkpointing logic to bypass the timeout. It worked, but maintaining it was painful. In hindsight, we'd recognize that as crossing below the compounding threshold: choosing the hack over thoughtful design. AWS Batch would have been the right call from day one.

The ephemeral nature of Lambda surfaces in ways beyond just timeouts: statelessness constraints, cold starts, and container lifecycle behaviors all require careful consideration. We developed patterns for working around these limitations, but that's a story for another time.

Serverless gave us the freedom to build fast; our maturity taught us when to outgrow it. That's the balance we continue to optimize for today.

The Enterpret Way

Every engineering journey leaves behind a trail of lessons, beliefs, and philosophies that define how a team thinks. For Enterpret, that philosophy is simple: small designs compound over time. We believe in designing systems that are simple yet extensible, that evolve rather than bloat, and that age gracefully as the company grows.

Core Beliefs

Our north star is clear: design systems that evolve, not expand. Small, thoughtful decisions made early can compound into significant technical leverage over years. Complexity is rarely inevitable; it's often a choice. We aim to choose clarity and extensibility, trusting that simple systems scale when designed with intent.

How We Build

Enterpret's engineering culture lives somewhere between pragmatism and philosophy. We debate finding the compounding threshold often. It's become our framework for every technical decision.

What we've learned is that great engineering isn't about writing code. It's about solving problems with the least code possible. We optimize for simplicity over cleverness, always thinking long-term. The best solution is rarely the most sophisticated one; it's the one that will still make sense years later. This discipline of choosing simple solutions to complex problems is what keeps our systems elegant as they evolve.

Advice to Other Teams

For startups and engineering teams navigating their own architectural decisions, here's what we'd share:

1. Keep infrastructure dead simple.

Stick to managed services and boring technology. Limit your surface area: fewer tools, fewer frameworks, fewer things to break. We didn't host a single piece of infrastructure ourselves for four years. Even our RPC layer, which we had to build due to API Gateway constraints, was a minimal investment at the compounding threshold: just enough to solve the problem, not a line more. The startups that survive aren't the ones with clever infrastructure; they're the ones that stayed focused on their product while the cloud did the heavy lifting. Boring technology will take you farther than you think.

2. Be ruthless about cost. It directly impacts runway.

Cost discipline isn't optional in the early stages; it's survival. Every optimization extends your runway to find product-market fit. Serverless helps when you understand your traffic patterns, but cost optimization requires discipline regardless of your infrastructure choice. We audited everything: memory allocation, timeout settings, service boundaries.

The principle is simple but hard to maintain: scrutinize every resource against actual need. Watch out for the silent killers. At one point, our CloudWatch bill exceeded our entire compute spend. Observability, data transfer, idle resources: these "small" costs compound faster than you think. Set spending alerts, review bills weekly, and question every line item. Small leaks compound into hemorrhages. Catch them early.

3. Make observability systematic, not optional.

We invested early in solid metrics, logging abstractions, and middleware so teams got tracing and metrics out of the box. This paid immediate dividends: faster debugging, confident deployments, and understanding production behavior with a tiny team. The key is making observability automatic through shared libraries and middleware, not relying on developers to remember. Good observability isn't about which tool you use; it's about consistent instrumentation across your entire system.

4. Design for horizontal scale from day one. It's not that much harder.

Many believe scalable systems require massive upfront investment. That's often untrue. We chose microservices early because we had clear domain boundaries and varying scalability requirements. Our ingestion services faced different demands than our analytics services. The key wasn't perfect architecture; it was hitting the compounding threshold. As we scaled, growth meant adding compute or database capacity, rarely rewriting core flows. The perceived effort delta between "quick-and-dirty" and "scalable" is often an illusion. A few good abstractions and clear service boundaries take marginally more time upfront but save you from rewrites later.

5. Don't chase cloud agnosticism too early.

It's tempting (cloud credits, switching flexibility) but the ROI rarely justifies it. We committed fully to AWS, leveraging its native ecosystem rather than playing on the intersection of portable abstractions. The intersection feels safe, but it's where innovation goes to die. When you constrain yourself to what works everywhere (like K8s), you're optimizing for the lowest common denominator, not for performance or simplicity. You get better systems by embracing what your cloud does best, not what every cloud does adequately. Migration is always possible later; acceleration happens when you bet deep, not wide.

Still Learning

AI has been at Enterpret's core since day zero, processing hundreds of millions of customer feedback records, delivering insights at scale. But the landscape keeps evolving. We're now building agentic architectures, pushing into new territories of what's possible. This evolution is teaching us new lessons about our old decisions. Some patterns from our serverless journey translate beautifully. Others need rethinking entirely. We're discovering new compounding thresholds, new tradeoffs, new ways to apply the same principles. The journey continues, and we're still learning what works.